Responding to an online learning critic

Last week’s post mentioned that we are still seeing influential observers criticizing online and hybrid learning mostly by conflating it with emergency remote learning. It linked to an article titled Online Schooling Is the Bad Idea That Refuses to Die, which at least has the positive attribute of being straightforward and honest about the writer’s views.

We are engaging with critics from time to time, and I wrote a long email to the author of that article. I’m using this blog post to reproduce my email as I’ve been asked a few times for how I respond in these circumstances, in case it helps any readers with their responses to online learning critics.

*****

Dear Dr. Gabor,

I’m writing in response to your Bloomberg piece titled Online Schooling Is the Bad Idea That Refuses to Die to make the case that online and hybrid schools and courses are in fact a viable option for millions of students in the United States—and in fact the best option for them in many cases.

<snipped some background blog readers are familiar with>

I’m putting sections of your piece in italics throughout this email to make clear the points that I am responding to.

Nearly all of the 20 largest US school districts will offer online schooling options this fall. Over half of them will be offering more full-time virtual school programs than they did before the pandemic. The trend seems likely to continue or accelerate, according to an analysis by Chalkbeat.

I agree, in particular that the trend is likely to continue. We are seeing a significant uptick in interest in online learning from many traditional districts.

School closings over the last two years have inflicted severe educational and emotional damage on American students.

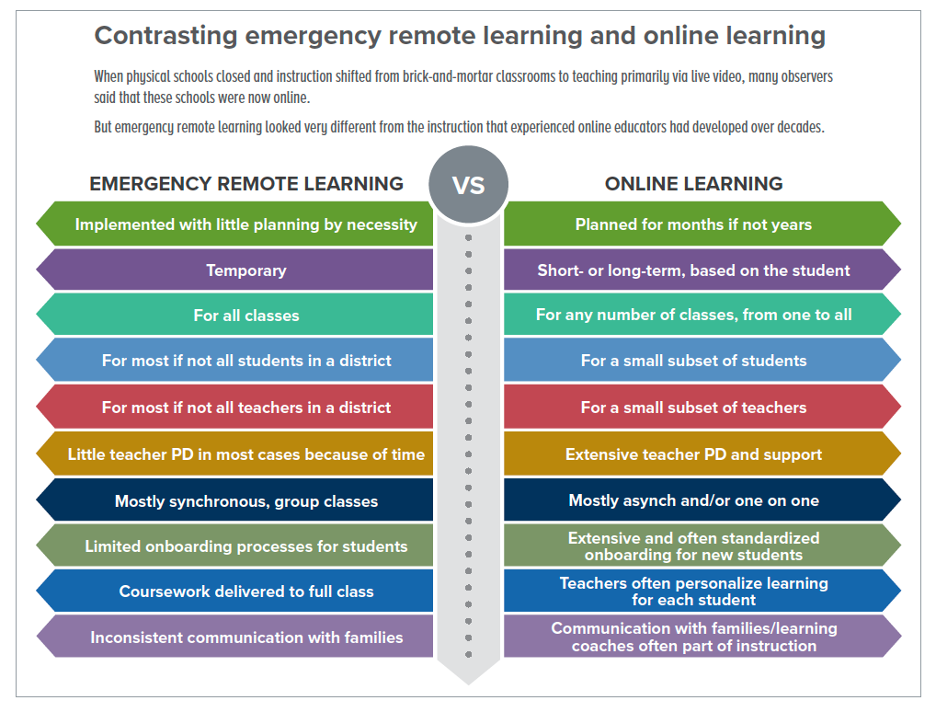

I agree—and it’s clear that the emergency remote learning that we saw implemented was often unsuccessful. In our annual Digital Learning Snapshot we contrasted emergency remote learning with online/hybrid learning using this graphic:

Schools should now be focusing on creative ways to fill classrooms, socialize kids and convey the joy of collaborative learning — not on providing opportunities to stay home.

This is where we disagree—although maybe less than you might think. I completely agree that schools should be focusing on providing creative, collaborative opportunities, and that these should be mostly based in physical schools. But it’s clear that learning from home has been the best option for millions of students pre-pandemic, and many more students and families found that they liked learning online during the pandemic.

These students learning online, or in hybrid schools, represent a wide range of cases. Some students have health issues. Others have fallen behind academically, or are seeking to advance at a faster rate than their traditional school allows. Some are focused on dual credit, internships, jobs, or other pursuits. They are highly varied, but have in common that they find that a non-traditional school, which is either online or a mix of online and face-to-face, is a better option for them. For student perspectives based on interviews, focus groups, and surveys, see “Why Students Choose Online and Blended Schools” on this page.

Historically, various forces have pushed for online education — not all of them focused on improving education. These include: the quest for cheaper, more efficient modes of schooling; the push to limit the influence of teachers unions by concentrating virtual teachers in non-union states; and a variety of medical and social factors that lead some students and families to prefer online learning.

I agree with much of this statement. In fact, we have made the case repeatedly that online and hybrid leaning are not cheaper modes of schooling, and using online options to save money is generally a bad idea. I disagree with the line about “concentrating virtual teachers in non-union states” because I think that statement gets cause-and-effect backwards. A state like Florida, with its public Florida Virtual School, demonstrates that there is demand for hundreds of thousands of students to take online courses. Does that demand from students and families not exist in a state like New York because there’s some reason NY students are different? Or does the supply simply not exist because of political and policy decisions? It seems more likely that the latter is occurring.

Since the pandemic, some virtual programs have reasonably stressed medically fragile students. But others are seizing on online education in a rushed effort to shore up public-school enrollments, which plummeted in some cities. The prevalence of these programs in Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Dallas and New York is particularly worrying, as they target poor and minority students who are likely to be particularly ill-served by online school options.

There’s no doubt that poor and minority students have been poorly served by online school options in too many cases. But shouldn’t the declining enrollments be seen as a signal that districts should be doing something differently?

We are finding an increasing number of districts starting hybrid schools that combine online and in-person options. The hybrid instructional model is showing success in schools like Crossroads FLEX in North Carolina, and Poudre Global Academy in Colorado.

Students in cyber schools do their coursework mostly from home and over the internet, with teachers often located in different states and time zones. There is little comprehensive information about the curricula, student-teacher ratios, how much actual teaching occurs, or what if any academic supports are provided by the schools.

I’m not clear on what “comprehensive” means in this paragraph. It is clear that there is a lack of general understanding of many of these issues, including within colleges of education and among policymakers. But at DLAC we host a research community that includes university professors and NGO representatives, as well as organizations such as Michigan Virtual University, which publishes extensively on these topics. In addition, teaching strategies, academic supports, and related topics are a focus of many DLAC sessions. Within the digital learning community, this information is widely available.

You touch on two areas that I won’t delve deeply into here, only because this response would turn into a mini-dissertation. These issues are 1) student outcomes in online schools, and 2) the role of companies that work closely with some online schools. I would be glad to discuss these issues further, or you might be interested in a report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office that I wrote about here. The bottom line is that the GAO raises these questions and finds the answers much less clear than critics maintain.

Finally, I’d like to focus on this paragraph and the closing points after it, because it is where I think a mistaken summary is given:

The adverse impact of the pandemic on the emotional well-being and social skills of children — one-third of school leaders reported a surge in disruptive student behavior during the past school year — is a cautionary lesson for online learning.

There is no question that the pandemic had tremendously negative impacts on students’ well-being and academic growth. There is also no question that attempts at emergency remote learning often did little to mitigate these issues. And, there is no question that most students are and will benefit from being back at a physical school.

But that is a very different conclusion than saying, as your article suggests, that online and hybrid options should be curtailed. Pre-pandemic, millions of students and families were choosing online and hybrid schools and courses. Post-pandemic, that number has gone up, as more students have discovered these opportunities.

Nobody in the online learning world would say that physical schools should not exist. I invite you to consider joining us at DLAC to talk with the 1500+ educators (along with a few students and parents), who would be glad to share with you why they believe that online and hybrid learning may not be the best option for every student, but should be available to every student.